Discrimination is one of the pillars of all organization structures that have, to this very day, evolved into the European Union as we know it today. The basic legal text of the Treaty Establishing the European Economic Community (1957) included a provision on the prohibition of discrimination on the grounds of sexual orientation as regards to employment and occupation. The scope of the application of EU law on anti-discrimination has been significantly broadened with the issue of the Directive for Equal Treatment in Employment and Occupation and the Racial Equality Directive. Finally, after the Treaty of Lisbon had entered into force, the Charter of Fundamental Rights of the European Union became legally binding and defined broader aspect of discrimination in Article 21.

Discrimination is one of the pillars of all organization structures that have, to this very day, evolved into the European Union as we know it today. The basic legal text of the Treaty Establishing the European Economic Community (1957) included a provision on the prohibition of discrimination on the grounds of sexual orientation as regards to employment and occupation. The scope of the application of EU law on anti-discrimination has been significantly broadened with the issue of the Directive for Equal Treatment in Employment and Occupation and the Racial Equality Directive. Finally, after the Treaty of Lisbon had entered into force, the Charter of Fundamental Rights of the European Union became legally binding and defined broader aspect of discrimination in Article 21.

Politics of conditionality and curtailment of discrimination

The enactment of the Law on the Prohibition of Discrimination is one of the most outstanding results of the politics of EU conditionality. EU conditionality can be divided into several stages, however, the most essential division refers to the conditionality prior to granting the candidate status (when conditions are somewhat set broadly), and conditionality after obtaining membership (when conditions are far more specific). It is quite clear that when enacting the Law the only condition of the European Union is for Bosnia and Herzegovina to enact the Law on the Prohibition of Discrimination which will generally adopt elements from the EU Directives.

Representatives and delegates at the Parliamentary Assembly of Bosnia and Herzegovina most likely would not have adopted the Law on the Prohibition of Discrimination had there not been for EU conditionality. Discussions during the adoption of this Law only further corroborate this claim. The sole fact that the enactment of this Law was one of the conditions for granting visa free regime for Bosnia and Herzegovina further attests to the importance of having a legal framework for the curtailment of discrimination that the European Union believes in.

Almost 6 years after the adoption of the basic legal text, the Law on the Prohibition of Discrimination is still in the focus of interest of the European Commission. Expanding the subject matters of the Structured Dialogue on Justice, the European Union singled out certain flaws in the very text of the Law, but it also stressed that one part of the politics of conditionality would be consistent implementation of anti-discrimination provisions through the adoption of a strategy at the state level. The Structured Dialogue is an intermediate stage which is, in essence, an integral part of the negotiations that follow after the candidate status has been granted. At this point, the requirements set by the European Union for B&H are far more specific.

Need for further harmonization of laws

What omissions did the European Commission identify? Propositions made at the 7th meeting of the Structured Dialogue called for B&H to ensure additional harmonization of the Law on the Prohibition of Discrimination with European Union law. It specifically noted that the Law did not define „age“ and „disability“ as prohibited grounds of discrimination, and that it should define grounds of sexual orientation and gender identity in accordance with the international terminology. Furthermore, the European Commission commended and stressed the importance of the amendments in terms of procedural provisions of the Law in order to ensure consistent enforcement by the courts and achieve legal security.

All these requirements, in essence, concern the increase of legal security. The inclusion of the prohibited grounds of „age“ and „disability“ is important, however, existing solution in Article 2 of the Law does not ban discrimination on these two grounds. Our legislator defined the list of the prohibited grounds far broadly than the requirements of the European Union called for. Consistent enforcement of the European Union law would require that the list of prohibited grounds be set most broadly. In the Charter of Fundamental Rights the list is set more narrow than it is set in the Law on the Prohibition of Discrimination even in terms of explicitly listed grounds of discrimination that include, for instance, memberships in a union or any other organization, sexual expression, and education. For the time being, our judiciary was inclined to consider cases of discrimination on other grounds such as disability in one of their first cases handled in accordance with the provisions of this Law.

When the list of prohibited grounds is set such broadly, the criteria for defining other grounds somewhat reduce legal security. In its practice the European Court of Human Rights has developed an approach for defining other grounds which requires that the grounds relate to the actual personal characteristics of individuals or groups which those individuals or groups make significantly different. Such requirement does not exist in the Law on the Prohibition of Discrimination and allows ordinary courts of justice to apply different, narrow or broad interpretations of it.

The European Commission also stressed the importance of having procedural provisions of the Law defined more unambiguously. The procedural aspects of the Law on the Prohibition of Discrimination have introduced significant amendments in comparison to other proceedings being conducted in accordance with valid laws on contentious procedure. These amendments have, for the most part, followed the guidelines from the two EU anti-discrimination directives and adopted the standards concerning the possibility of filing collective lawsuits and the burden of proof rules.

These two procedural standards in particular are the biggest contribution of the Law. The contentious procedure reform in B&H, that occured in the wake of 2000, resulted in the principle of accusation becoming the prevailing principle of every lawsuit. According to this principle a plaintiff has to prove entirely that the respondent had acted against the law, that is, had violated specific contractual obligations. The respondent may decide accordingly to disprove evidential value of facts suggested by the plaintiff without producing any counter evidence. If the plaintiff cannot produce all the necessary evidence, his/her lawsuit will fall through.

Observing the application of the principle of accussation from the standpoint of discrimination cases in which possibilities of determining truthful facts are impossible without active participation of the respondent, since in most cases, necessary evidence is in the possession of a person who discriminates. The burden of proof rules distribute the obligation to prove the claim between the plaintiff and the respondent. According to this rule, which is strictly applicable in cases of discrimination, if the plaintiff corroborates their claims with facts, the burden of proof shifts onto the respondent. It follows that by applying the standard of proof based on the determination of prima facie or the assumption that descrimination exists, the court should request that the respondent prove they did not discriminate the plaintiff, that is, it did not violate plaintiff’s right to equal treatment. This rule, to a great extent, allows filing lawsuits against discrimination for those cases in which persons, who thought they were victims of discrimination, simply failed to provide sufficient evidence.

What is disputable with the existing solution in Article 15 is the fact that the standard of proof has not been entirely defined. Directives, the practice of the Court of Justice of the European Union, and the practice of the Constitutional Court of B&H assert that this standard must be defined in such a way that when the court „based on the submitted evidence can assume that it is a case of discrimination,“ it should distribute the burden of proof. This standard is unclear and allows inconsistent application in practice.

The rule on possibility of filing a collective lawsuit has started a small revolution in the methods of protection against discrimination. According to this rule, organizations registered for the protection of human rights can file a lawsuit on behalf of a group of persons who need not to be identified, i.e. need not to be active participants in the proceeding. This broadens active legitimation beyond the general rule according to which a lawsuit can be filed only by the person that is in a lawsuit with the respondent. This possibility has already helped initiate several important strategic cases where the lawsuit regarding the phenomenon of „two schools under one roof“ is singled out as probably the most crucial one. Filing individual lawsuits, in this and other cases in which specific groups of persons are considered to be discriminated, would prove to be inefficient and complicated, and thus, this rule contributes to legal security. Nonetheless, the interpretation of this provision by the courts was obviously different, hence, this provision should be specified.

Efficient protection against discrimination

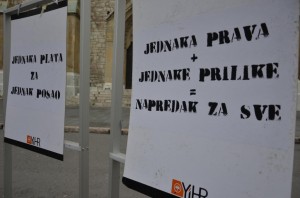

The Law follows the objectives of the EU directives in regards to defining the outlined impact of the Law. Article 1 determines that the objective of this Law is to establish a framework to achieve equal rights and opportunites for all persons in Bosnia and Herzegovina, and to organize the system of protection against discrimination. The European Union has not analyzed the success of these objectives yet, since the attention is still focused on the enactment of a thoroughly harmonized Law on the Prohibition of Discrimination with European Union Law.

The practice of courts concerning efficient protection, which should be guaranteed with this Law, has not been completely achieved yet. Analyzing cases that have been considered by the courts so far, it can be concluded that the practice is quite unbalanced. Apart from this and the fact that cases of discrimination are emergency procedures, the courts still do not act urgently. In the appeal filed by the under age I.Š. No. AP-1859/11, the Supreme Court of B&H has determined:

„violation of the right to fair trial (…) in regards to the right to deliver a decision within a reasonable time in the situation when the first instance decision has not been ruled after one year and nine months in the emergency procedure, in which personal status is being resolved and which is of utmost importance for the appellant.“

Simultaneously, in the ruling of the Cantonal Court in the case regarding the phenomenon of „two schools under one roof“ the Supreme Court of FB&H has proved wrong implementation of the Law on the Prohibition of Discrimination in terms of deadlines and procedural omissions when the Court engaged in the merits.

The analysis of these and other legal cases indicates that efficient protection against discrimination has not been achieved yet. Even when the Law becomes completely harmonized with the directives, efficient protection will not be guaranteed because it requires consistent enforcement of the Law by the courts.

Apart from the past activities, specifically the education of judges regarding the enforcement of the Law which was conducted by the centers for education of judges and prosecutors, very little has been done in order to ensure necessary capacities of courts which would respond to the challenges of discrimination. After the accession to the European Union in certain domains this will imply direct enforcement of the directives for those situations in which the directives would not be accurately transferred into the legal system of B&H by the application of the principle of direct effect. In such situations individuals could come before the courts in B&H and directly appeal to the text of the directives in order to assert their rights. After the accession of B&H to the European Union there shall be an additional requirement that the anti-discrimination law be interpreted in accordance with the position of the European Court of Human rights in terms of the application of directives which will further complicate operation of courts.

How to ensure efficient protection against discrimination?

Analyzing the enforcement of the Law so far, it is obvious that B&H, despite having a relatively satisfying legal framework, still has not implemented an efficient system of protection against discrimination. Certainly, any significant progress will not be achieved through the passive treatment of this obligation.

One of the solutions is the introduction of a specific public policy that would concentrate on the prevention and struggle against discrimination. The European Commission in their 2014 Progress Report on Bosnia and Herzegovina, and the UN in their last report of the Universal Periodic Review for Bosnia and Herzegovina from June 2014 have recognized the need for the introduction of a specific public policy.

It is obvious that the European Commission has recognized the lack of activity which hampers efficient protection against discrimination, i.e. realization of equal opportunities. Introduction of the public policy, i.e. Strategy would ensure coordinated and proactive approach to the efficient protection against discrimination in order to meet the pre-accession and post-accession requirements.

The question is does Bosnia and Herzegovina have adequate available capacities to ensure development a comprehensive strategy, and more importantly, to execute its consistent application in practice? Obviously, the key element in this process will be the support of the European Union, and the European Commission has made it clear that financial support will be granted only for those projects concerning the implementation of national sector strategies. It is to be expected that the strategy directed at the curtailment of discrimination would be financially supported from the pre-accession instruments of the European Union.

Sarajevo, March 2015.

Initiative for monitoring the European integration of B&H